A multinational collaboration between the University of Southern California, Lizzia Raffaghello at the G. Gaslini Institute in Italy and the laboratories of Alessio Nencioni at University of Genova, showed that a less-toxic class of drugs combined with fasting has anti cancer potential and may be effective against colorectal cancer, along with lung and breast cancers. The results, published in the journal Oncotarget, suggest that a low-toxicity drug combined with fasting could work as an alternative to chemotherapy.

A multinational collaboration between the University of Southern California, Lizzia Raffaghello at the G. Gaslini Institute in Italy and the laboratories of Alessio Nencioni at University of Genova, showed that a less-toxic class of drugs combined with fasting has anti cancer potential and may be effective against colorectal cancer, along with lung and breast cancers. The results, published in the journal Oncotarget, suggest that a low-toxicity drug combined with fasting could work as an alternative to chemotherapy.

According to Valter Longo, senior author working at the University of Southern California, this approach was proven to work in humans, revealing that fasting may be used as a potent component of a long-term strategy to address cancer.

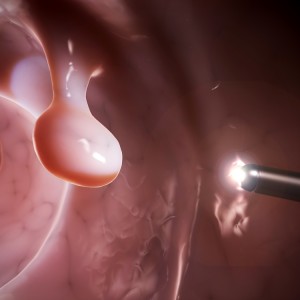

In 2011, 135,260 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the United States (70,099 men, 65,161 women) and 51,783 people died because of the disease (26,804 men, 24,979 women).

To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of cyclic fasting in cancer treatment, human clinical trials are currently underway in Europe and in the United States. “Like every other cell, cancer cells need energy to survive and keep growing. But cancer cells are fairly inflexible about how they produce that energy, which gives us a way to target them,” explained Dr. Longo, director of the USC Longevity Institute.

Cancer cells are highly dependent on sugar or glucose (obtained from food) as a source of energy. In contrast with healthy cells, cancer cells burn much more glucose to fuel their tremendous rapid growth, which renders them more vulnerable and highly influenced by any interruption in sugar supply. In the case of glucose deprivation, cancer cells rely on an emergency backup process in which they activate specific kinases that support their proliferation process.

Dr. Longo and his collaborators found that these metabolic alterations allow cancer cells to generate toxic-free radicals, leading to cancer cell death. Furthermore, energy-generating kinases can be blocked using kinase inhibitors that stop tumor cells’ ability to produce energy. Such kinase inhibitors have already received approval by the FDA. “However, kinase inhibitors, though much less toxic than chemotherapy, can still be toxic to many cell types. Fasting makes them more effective, meaning that patients would have to use them for less time to achieve the same results. Although we have not yet tested this, we anticipate that fasting will also reduce the toxicity of kinase inhibitors as it reduces that of chemotherapy to normal cells,” Dr. Longo concluded.